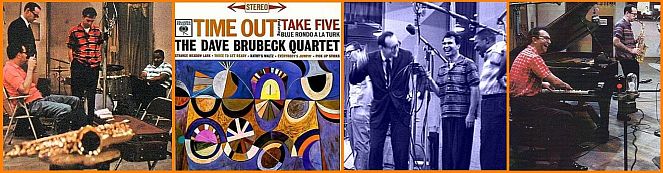

Extract from "Take Five - The Private and Public Lifes Of Paul Desmond"

©Doug Ramsey. Reprinted with the permission of the author; copyright protected; all rights reserved.

After “Take Five” became one of the most familiar pieces of music in the world, Desmond tired ![Paul Desmond - take five doug ramsey[1] Paul Desmond - take five doug ramsey[1]](http://dbj.silverink.ie/download/1/Images/Images%20For%20Text/Paul%20Desmond%20-%20take%20five%20doug%20ramsey[1].jpg) of questions about it and amused himself by concocting stories about the piece’s origins. His favorite version linked it with his gambling habit. He told people that he was inspired by the rhythmic sounds that slot machines make—down, back, click-click-click.

of questions about it and amused himself by concocting stories about the piece’s origins. His favorite version linked it with his gambling habit. He told people that he was inspired by the rhythmic sounds that slot machines make—down, back, click-click-click.

“Have you ever heard that?” Dave Brubeck said, laughing. “I read that somewhere and I said, ‘Come on, Paul, no.’ It was Joe Morello who gave him that rhythm.”

Morello said that in concert he used to go into 5/4 time in the drum break of a Brubeck piece called “Sounds of the Loop,” which the group recorded in 1956 in its album Jazz Impressions Of The USA.”I’d just mess around in 5, go from 5/4 to 7/4, and I guess they hadn’t heard that kind of thing before, so I kept saying, “Come on, Dave, why don’t you write something in 5/4? He never did, so Paul said one night, ‘Oh, shit, I’ll write something.’ We were rehearsing up at Dave’s house one time, and Paul came in with that. So, we recorded the thing in the studio at Columbia, and I think it was the first take or the second take, and Dave was playing the vamp. I got more comments on that darn drum solo. I hear it every day somewhere, so it was a very lucky thing. It was my idea. Everybody made a lot of money but me.”

The question of initial inspiration for “Take Five” aside, in a 1976 interview on Radio Canada, Desmond gave Brubeck ultimate credit for the radical idea in 1959 of recording an album of pieces in unorthodox time signatures. Brubeck had written for the Octet in unusual meters as early as 1946.

The question of initial inspiration for “Take Five” aside, in a 1976 interview on Radio Canada, Desmond gave Brubeck ultimate credit for the radical idea in 1959 of recording an album of pieces in unorthodox time signatures. Brubeck had written for the Octet in unusual meters as early as 1946.

“I still think, basically, it was a dubious idea at best,” Desmond said, “but at that point we had three or four albums a year to get done, and we’d done all our tunes that we’d put together, and standards and originals of Dave’s and he said, ‘Why don’t we do this album and do all different time signatures?’ And I said, ‘Okay.’ I was always argumentative. And, for some reason, I lucked out. I really did. It was sort of like Keno.

‘Okay, we’ve got 2/4, 3/4, 5/4, 6/4, 7/4, 8/4, whatever. Why don’t you take 5/4?’ And I wrote Take Five and I realize now, that was a genius move on my part. At the time, I thought it was kind of a throwaway. I was ready to trade in the entire rights of ‘Take Five’ for a used Ronson electric razor. And the thing that makes Take Five’ work is the bridge, which we almost didn’t use—I shudder to think how close we came to not using that. I said, ‘Well, I’ve got this theme we could use for a middle part, and Dave said, ‘Well, let’s run it through,’ and that”—Desmond whistled the first four bars of the bridge section—“is what made Take Five.’” (Paul Desmond, Radio Canada, probably June, 1976)

The piece had no name when Desmond brought in the two themes. Brubeck came up with the formula for combining them into AABA form and provided the title. In a conversation with Gene Lees, Desmond elaborated on the structure and content of the piece.

“I had the middle part kind of vaguely in mind. I thought, ‘We could do this, but then we’d have to modulate again, and we’re already playing in 5/4 and six flats, and that’s enough for one day’s work.’ Fortunately, we tried it, and that’s where you get the main part of the song.

The bridge is a chromatic reduction of the opening phrase of the Johnny Burke-Jimmy Van Heusen popular song “Sunday, Monday, or Always,” a 1943 hit for Bing Crosby, a piece that Desmond frequently quoted in solos. His adaptation of it is in ideal contrast to the first theme and creates an exquisite balance between the two sections.

Simplicity may have been a factor, but the public was taken with the piece’s irresistible good feeling, and memorable solos by Morello and Desmond. Ted Gioia expanded on that thought. After writing of the “tired format” of the Brubeck recordings that preceded Time Out, he praised the album’s “burst of creativity” as “nothing short of staggering.”

“This was not only the most financially successful album of Brubeck’s career, but was also an immense artistic success,” Gioia wrote. “This latter fact may well have been hidden under the critics’ continued gripes about Brubeck’s dazzling rise to even higher heights of stardom, yet the snide comment and put-downs did no lasting damage. This album is still a delight to listen to a generation later, and not just because of the odd meters—others have come to master them with greater ease since 1959—but because of their winning incorporation into a series of exceptional and fresh sounding compositions. Perhaps no other jazz album of the decade exuded so much enthusiasm and such a sense of unbridled fun.” [Ted Gioia, West Coast Jazz, Oxford, 1992, p.20.]

“Take Five’s” popularity came as a surprise to everyone involved; Desmond, who composed it; Morello, who inspired it; Brubeck, who, as Morello requested, “kept that vamp going;” Wright, who loved playing in 5/4; and, most of all, Columbia Records, which hated the idea until the company realized that it had been looking a prize-winning gift horse in the mouth. Nonetheless, the song did not hit immediately. Columbia President Goddard Lieberson ordered a single of “Take Five,” with “Blue Rondo a la Turk” on the other side, but it took Columbia eighteen months to issue a version edited for juke boxes and radio airplay. Brubeck asked Columbia to push both tunes equally, but Columbia argued that there had to be an A side and a B side. The company decided to make “Take Five” the A side because the title was catchy and “Blue Rondo a la Turk” was too long for juke box menus. It was not until 1961 that “Take Five” became omnipresent at home and abroad.

“Take Five’s” popularity came as a surprise to everyone involved; Desmond, who composed it; Morello, who inspired it; Brubeck, who, as Morello requested, “kept that vamp going;” Wright, who loved playing in 5/4; and, most of all, Columbia Records, which hated the idea until the company realized that it had been looking a prize-winning gift horse in the mouth. Nonetheless, the song did not hit immediately. Columbia President Goddard Lieberson ordered a single of “Take Five,” with “Blue Rondo a la Turk” on the other side, but it took Columbia eighteen months to issue a version edited for juke boxes and radio airplay. Brubeck asked Columbia to push both tunes equally, but Columbia argued that there had to be an A side and a B side. The company decided to make “Take Five” the A side because the title was catchy and “Blue Rondo a la Turk” was too long for juke box menus. It was not until 1961 that “Take Five” became omnipresent at home and abroad.

“We are innocent of trying to make a hit record,” Brubeck told Down Beat. “When I get most skeptical about so-called popular music, and the public, and the radio stations, I think about “Take Five” and “Blue Rondo” and feel that the public can go for some pretty good things.”

Despite Brubeck’s characteristic optimism, it was a monumental, and rare, instance of music triumphing over conventional wisdom and the accounting mentality of the record business, and it happened in the nick of time. Within a few years of “Take Five’s” success, the segmented popularity-charting of the music industry, targeted marketing practices of record companies and mandated playlists at radio stations had strangled the possibility of an unconventional record driving its way to the top by force of its musical merit and attractiveness. The disc jockeys who exposed “Take Five” to a receptive public simply because they liked it were soon to lose their freedom to choose the records they played on the air.