Wall St. Journal - Dave Brubeck’s ‘Gates of Justice’ Is a Prayer for Healing

The oratorio by the jazz pianist, first performed in 1969, is a plea for harmony between black and Jewish communities in the U.S. that deftly intertwines musical traditions.

By Stuart Isacoff - Wall Street Journal ©

Feb. 24, 2023

When an assassin’s bullet felled Martin Luther King Jr. on his balcony outside a Memphis motel room on April 4, 1968, it also tore through the nation’s social fabric. In the aftermath a festering racial divide deepened even further, including between America’s black and Jewish communities, which once found a common bond in fighting social injustice. In a spirit of healing, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and the College Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati jointly commissioned a musical work from the pen of jazz great Dave Brubeck. The resulting oratorio, “The Gates of Justice,” was unveiled at the dedication of a new building for Cincinnati’s Rockdale Temple on Oct. 19, 1969.

A finely crafted, beauteous plea for universal brotherhood, it was recorded and released on Decca Records before the end of that year. Now it can be experienced live again on Feb. 26 at the University of California, Los Angeles (and will be streaming on its school of music’s website), along with a scholarly conference the following day, with a repeat performance at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles on Feb. 28. It is all being presented under the rubric “Music and Justice” by the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music and the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience.

But this will be no mere attempt at historical repetition: The concert will begin with new music by pianist and composer Arturo O’Farrill and several other artists recognized for contributions to black or Jewish music.

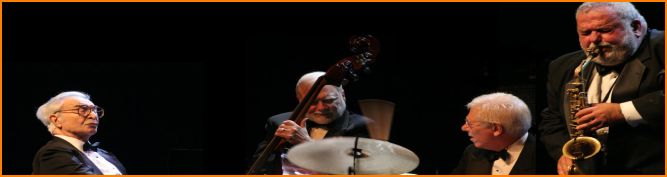

Brubeck’s composition, a 14-section oratorio, weaves together elements from both Jewish and African-American traditions, featuring a Hebrew cantor and a black singer, along with a large mixed chorus, brass, organ, assorted percussion, and a jazz piano trio. It incorporates such textual sources as the Bible, the speeches of King, and the writings of the Jewish sage Hillel, all compiled and shaped by Brubeck’s wife, Iola. The premiere featured the composer at the piano. At UCLA three of Brubeck’s sons, Darius, Chris and Dan, will form the jazz trio.

Like George Gershwin and Louis Armstrong before him, the composer found a shared aesthetic between Hebrew chant and the blues—a musical quality the Forward newspaper once described as “the cry of anguish of a people who had suffered.” The melodies capture the intended character of the soloists, making use of Middle Eastern modes for the melismatic cantor (employing the trademark lowered second of the scale along with the major third), and fervent, gospel-tinged lines for the baritone. The pace is masterfully varied, shifting from the highly propulsive to the deeply introspective (the latter as in the plaintive “Lord, Lord,” which was also recorded independently by Carmen McRae in 1961).

The work’s emotional tone is often jubilant, animated by restless, syncopated dance rhythms, and colored by rich, thick harmonies (superimposing tones from multiple keys), along with antiphonal passages in which the voices and instruments alternate. Brubeck’s jazz background surfaces at climactic moments, and it is especially powerful in the penultimate “His Truth Is a Shield,” which offers breathlessly fast brass fanfares, then slows into a swinging blues style. This hybrid approach (classical/jazz) is evident throughout, as in the third section, “Open the Gates,” which joins the two vocal soloists together in a beseeching prayer before exploding into an energetic interlude, featuring boisterous piano and tumbling choir lines, and eventually settles into a soft chorale. The work ends with a strong, full-voiced coda.

Dave Brubeck was the perfect composer to bridge all the divides: a fighter against racial prejudice, especially on behalf of his black bandmate, bassist Eugene Wright ; a deeply spiritual man with a reputation for kindness, whose earlier oratorio, “The Light in the Wilderness” (1968), had as its central tenet “Love Your Enemies”; a musician on the cutting edge, whose 1959 album, “Time Out,” featured unusual, sophisticated time signatures but nevertheless attracted a wide audience and became the first jazz recording to sell a million copies.

Brubeck was not Jewish. Nevertheless, he named three Jewish teachers as great influences: philosopher Irving Goleman, composer Darius Milhaud, and Jesus.

The original recording of “The Gates of Justice” opened with the blowing of a shofar, a ram’s horn traditionally used in Jewish prayer services to signal a spiritual awakening. A 2001 re-recording of the work, produced by Milken and still available on the Naxos label, substituted the French horn, an instrument whose pitch is more easily controlled. Chris Brubeck will be bringing his father’s collection of shofars to the California performances. Perhaps the UCLA presentation will help spur the kind of awakening we all still desperately yearn for.