The Guardian, UK

Nearly 50 years ago, Take Five made Dave Brubeck both a hero and a villain. John Fordham on the man who gave jazz a classic twist.

Brubeck grew up on a California ranch, learned classical piano from his mother, and switched from veterinarian studies to music after his first college year. The College of the Pacific's music faculty thought he was gifted, but so bad at sight-reading that, before they'd give him a degree, they made him promise never to teach music.

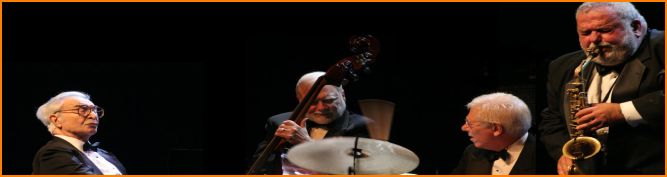

A conscientious objector in the second world war, he was given an army band to run instead, studied with the classical composer Darius Milhaud, and founded his first quartet in 1951 - with a young alto saxophonist called Paul Desmond, whose playing sounded like a soft whisper. A mid-50s album, Jazz Goes to College, sold over 100,000 copies and made Brubeck the first jazz musician to be featured on the

cover of Time.

Driven by Joe Morello, a phenomenal polyrhythmic drummer who seemed to have a separate brain operating each one of his limbs (Take Five had been spawned by one of his practice routines) the Brubeck group made complex rhythms and classical devices, like the rondo and the fugue, its trademark. The album Time Out, released in 1959, was a huge seller and the group globe-trotted for a decade, not splitting until 1967. Brubeck's awards, citations and concerts for world leaders (he even played the 1988 Reagan-Gorbache Moscow summit) became too numerous to count.

Long interested in large-scale composition, Brubeck uncorked a torrent of crossovers. The list still lengthens, with tomorrow's Christmas gig including La Fiesta de la Posada, a choral piece drawn from the Californian's experiences of Mexican festive music, and featuring the London Symphony Orchestra and a raft of classical singers. The second-generation Brubeck’s also join the patriarch on a jazz set that pianist Darius Brubeck says "we might figure out on the night".

Darius, a jazz teacher, composer and performer, recalls a conversation he had with the musicologist Gunther Schuller, who championed the work of radicals like Ornette Coleman and George Russell, and coined the term "third stream" in the 1950s to describe crossovers of classical music and jazz. "Schuller said you don't hear the term 'third stream' used any more," Darius says. "Because now it's everywhere. It's not a style, but a skill-set - it just means musicians who have the flexibility to play outside specific idioms. Dave was controversial from the standpoint that people wanted to stick to a certain type of narrative about jazz, and what he was doing contradicted it."

London Symphony Orchestra musicians Gerald Newson and Maurice Murphy,both of whom have worked extensively with Brubeck senior, confirm that transition and Brubeck's part in it. "He was one of those who put jazz on the concert platform, and encouraged musicians from different disciplines to work together," says Newson. Murphy, the orchestra's principal trumpeter, says: "Freelance sessions these days are likely to have two jazzers and two straight players in the trumpet section, not all classical. We learn from each other, and there's a total

mutual respect. I think Brubeck has had a lot to do with that over the years, he makes different styles blend wonderfully. And on top of all that, he's a total pro, and such a nice, gentle guy."

But why, at 85, does Brubeck stay on the roundabout of hotel rooms and departure lounges, when he could be taking in the view from his studio window in Connecticut? "In jazz, if you don't have a working group, you can't improvise," Darius Brubeck says. "Then what you do just becomes your act. So that's a stark choice for him. Not going on the road means you don't play jazz, and he doesn't want to give that up.

I'm sure when the logistics don't work, it gets to him. But he's very comfortable with where he is and what he's doing, and he's carrying both his loyal audience and a new generation of fans with him."

In 1959, Dave Brubeck was the first artist to sell a million copies of a jazz instrumental. He was on the cover of Time magazine and played in front of presidents and popes. Take Five is still one of the world's best known jazz tracks, and Brubeck, who turns 85 this month, is still composing and touring.

Yet Brubeck continues to be more interested in the present and the future than many of his fans. He's still between the rock and the hard place he's occupied for most of his five-decade career. When the wiry, donnish, California-born jazz pianist played Portsmouth in 2003 on one of his endless world tours, he took one look at the sea of white hair in his audience and threw half his new tunes off the set-list. He's never stopped composing, but those old hits are what his audiences expect.

That's how it's been since his catchily tricksy jazz instrumentals perched alongside Ben E King and the Everly Brothers in the pop charts of the early 1960s. Since then, the classically-influenced Brubeck has written for choirs and symphony orchestras, for ballets and chamber groups, for his own long-running quartet and the ensemble featuring his three sons that gets together for high days and holidays, like tomorrow's Christmas show at London's Barbican.

Take Five has found its way into movies like Mighty Aphrodite, Pleasantville and Constantine, and into the aural wallpaper of restaurants and elevators everywhere - but it still sounds playfully fresh, turning the remarkable trick of swinging freely despite a treacherous metre. Composed by Brubeck's then saxophonist Paul Desmond, Take Five was the triumph among a remarkable group of instrumentals the Brubeck group recorded at the height of its stardom between 1958 and 1967. They featured unconventional rhythms (Take Five was in 5/4, Blue Rondo à La Turk in 9/8), coolly jazzy, smoky-sax melody, percussively emphatic piano-playing, and often a smattering of classical borrowings.

But Brubeck's journey had its hitches. Some jazz diehards loathed his music for its apparent betrayal of jazz's bluesy roots, and for what they saw as dilettantist flattery of an aspirational audience in its classical references. The British critic Benny Green remarked in 1958 that "posterity may well wonder how such a legend should have come about in the first place".

Posterity, however, has decreed that Brubeck today stands alongside Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and a handful of others as fully functioning practitioners who several generations of listeners now realise made a difference. With the heat of the jazz-versus-classical battle long subsided, Brubeck's best pieces are now widely acclaimed for their originality, openness to many genres and cultures, and bold exploration of rhythmic adventures that bridge Africa and Europe.