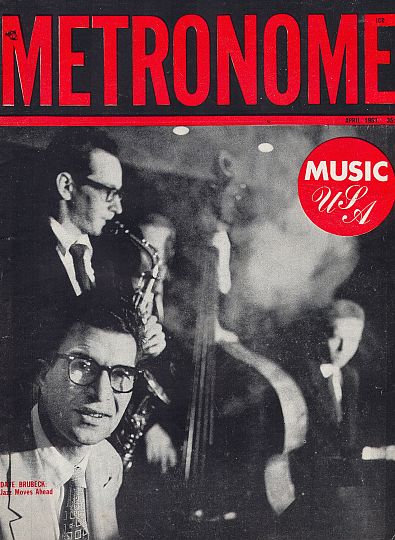

Metronome

Jazz Moves Ahead - Batty Ulanov

It may seem strange-but I'm going to start this piece on the merits of Dave Brubeck by discussing an organ recital I attended the second of February in New York. The organist was Jeanne Demcssicux, a French musician of more than passing excellence. The music played was that of Purcell, Bach, Cesar Franck, Widor and three contemporary French composers, including Mlle. Demessieux. It's the last group I want to say a few words about - Olivier Messiaen, Jean Berveiller and the performer. Their music is so close in spirit and direction to our music - jazz, that is - that an outline of salient points cannot help but be relevant to the subject.

It may seem strange-but I'm going to start this piece on the merits of Dave Brubeck by discussing an organ recital I attended the second of February in New York. The organist was Jeanne Demcssicux, a French musician of more than passing excellence. The music played was that of Purcell, Bach, Cesar Franck, Widor and three contemporary French composers, including Mlle. Demessieux. It's the last group I want to say a few words about - Olivier Messiaen, Jean Berveiller and the performer. Their music is so close in spirit and direction to our music - jazz, that is - that an outline of salient points cannot help but be relevant to the subject.

The Messiaen piece was his Banquet Celeste, a slow, solemn investigation of a religious subject, rather free in its melodic variations, substantially conventional in its bass line. The Berveiller Cadence could have been written by any well-equipped jazzman; with this exception its syncopated figures would have had far more rhythmic life if they had been scored by Ralph Burns, say, or Eddie Sauter.

The Demessieux pieces could only have sprung from a solid knowledge of the organ, a knowledge that could only have been synthesized by years of improvisation on that considerable instrument. The effect of this second half of the program was summed up in Mlle.

Demessieux's last effort, a series of improvisations on themes handed to her on the spot. Structured, of a sumptuous modern style, elegant to the ear, these virtuoso variations proved once again that improvisation is the life-blood of music, whether it is traditional in style or not, however conventional or unconventional its finished form. Furthermore, this performance-as any good modern French organist or any top-notch modern jazzman’s showed that the great improvising tradition of Bach is still very much alive. All of which brings us right around to Brubeck.

More than any other contemporary jazz musician, Dave is directed in his playing by his studying background. You're not always aware of the impending M.A. degree under Milhaud. You don't always know that this man has devoted hours to counterpoint, harmony, theory, composition and related disciplines. But the signs are plentiful. A little canon here, a bop fugue there. A little melodic development somewhere else, a grand exposition elsewhere still. The texture is out of the great classical composers; the base upon which it rests is jazz motion. And all of this-minus the implied compliments-Dave knows, and knowing it strives to resolve the necessary conflict that arises between the stresses of classical music and the strains of jazz.

Perhaps conflict isn't the right word to describe the tricky balance; tension would be more accurate, an inner tension around which the best of the Brubeck Trio and Quartet and Octet has always revolved. It comes most clearly to Dave's mind in his dissatisfaction with the terrible limitations of three-minute jazz form:

"The best I've ever been able to do to solve those limitations is to set up my own. My basic idea-you know this-is to take the opening phrase of a tune, the first few measures, and use only those for extended variation."

Now Dave has a few other solutions. "Two-sided pieces. Maybe they break into three minute segments, too, but there's a lot more continuity that way." And there's also the suite. "I've got one coming up; ten short things-minute to a minute and a half-that go together. Just the piano alone, where I feel most comfortable doing this kind of thing."

He knows, as every thinking jazz musician of today does, that he can't go on in this hit-or-miss fashion, hoping always that he has found a temporary answer, that he has plugged the gap, expanded just enough, developed beyond the immediate limitations-but not too far. Appearances have often suggested that Dave has been playing it safe in just that way: achieving more and more skill as a night club pianist and leader, his records increasing in invention and daring, but rarely beyond the margin of safety.

Those appearances weren't-aren't-always just. A successful jazz trio or quartet is only a step beyond one that merely works regularly: it must play recognizable tunes, it must compete with comedians and singers, its level must be somewhere between the American ideal-great music-and the Soviet ideal-music that the workers can whistle.

Dave has remarkably often hit that likable, livable middle plane, where you enjoy yourself musically and manage at the same time to provide for the loved ones. He is restless, however, and a man who can't stop thinking. He knows he's made a comfortable reputation and now can adjust some of the playing to the thinking. A recent afternoon with him at my home produced the words above and some more of similar quality.

"Look," he said, "we were doing wonderful things years ago." He was referring to the San Francisco octet of 1947 and conferring the high praise not upon himself but on his colleagues. "We're bringing out an album to show it--Old Jazz From San Francisco."

The crack at New Jazz From Sweden is implicit, if not intended, and fair. He played the records for me and like those I heard in San Francisco in 1949, they swing, they have imagination and wit and a fine ease within very general time limitations. "Now," Dave continued, after we listened to the records, "I'm going to try some other experiments. There's that piano suite. I'm working on a string quartet with a jazz movement, a Western movement.

The sounds of this country----Dave's major problem, as it is of many other jazzmen, is to find subject-matter that has depth and breadth, in which one can get somewhere besides a release and a final eight bars that sound like the release and last eight of all the other tunes, or most of them anyway. He can't change the notes and the keys of which they're a part; he's stuck with the diatonic scale, and pleased about it. He's friendly to atonality only to a point, and essentially conservative in his harmonic ideas, not conservative by jazz standards, but almost strait-laced by comparison to the twelve-tone school, those influenced by Schoenberg and Berg and Webern and their jazz counterparts. His teacher is Darius Milhaud and his tastes are like those of his teacher. And this, I think, is all to the good.

We need in jazz at this point musicians of background and invention who can handle jazz at this point and take it along the necessary next steps. We'll always have room for the wild men, the boys who can only see the ultimate development. Right now, however, our pressing need is for this move, Dave's move. What is really encouraging is that Dave knows better than most musicians. where we are in jazz, approximately where we can go next, and with what means.

Few musicians are so stimulated by their craft, so stimulating in what they do with it. It is fitting that he, of all people, should be placed in so responsible a position.