Downbeat

Dave Brubeck was a cowboy.

"That's the ranch house and barn," he said, pointing to a painting near the entrance of his home in Wilton, Conn. A simple Western scene, it's the yard of his father's California cattle ranch. "When I wake up, I look right at a painting over the fireplace in my bedroom. It's like that one, but a different scene. It's the first thing I see every morning. And there's a picture of my dad on horseback with me. I never get away from that wonderful life. It's always with me."

Brubeck, 82, looks like an emperor more than a cowboy or jazz master. Tall and lean, his profile rises majestically across his high brow to silver hair that always seems wind swept. With or without his hallmark glasses, his face is time-worn but mighty like the mountains where he herded cattle as a kid.

"You must have been sculpted," I said. He smiled and pointed above us. There, on a balcony over his music room, is his head on a pedestal. "That's the plaster mold," he said. "The real sculpture is at Mills College Music Library."

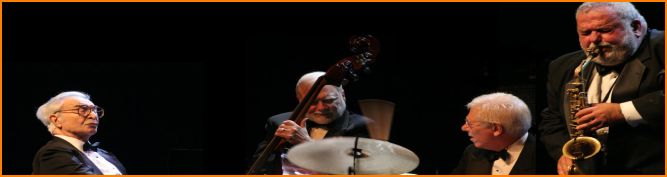

One of the most popular and honored jazz musicians, Brubeck is almost always on the road. All this year he's been playing across the United States, plus he had a triumphant tour of the U.K. He's already booked for an 85th birthday concert with the London Symphony Orchestra. His newest album, Classical Brubeck (Telarc), is a double-disc with three of his larger religious works, recorded with the LSO, the London Voices, a boys choir and the Dave Brubeck Quartet. His most recent jazz album, Park Avenue South: Live At Starbucks (Telarc), is a live recording of the quartet (drummer Randy Jones, bassist Michael Moore and saxist/flutist Bobby Militello) playing standards, some new originals--Brubeck is always composing--and, inevitably, "Take Five."

In May, Brubeck had recently returned home after more than 50 days making music around the world. While sitting at his grand piano in the house he shares with Iola, his wife of more than 60 years, we could see through glass walls his beautiful garden and woods. Along one wall near the piano is a virtual gallery of his musical life, especially paintings and portraits of his friends and inspirations. Duke Ellington. Count Basie. Brubeck with Oscar Peterson on a framed 1997 cover of DownBeat. Leonard Bernstein looking over a manuscript with Aaron Copland. Composer Darius Milhaud, his mentor as a young music student. And another of his idols, Fats Waller.

"I was doing a TV show last year in England," Brubeck said. "[The interviewer] asked me who was my first influence. I said, 'Fats Waller.' I got a dollar a day from the ranch and I spent 48 cents on 'Let's Be Fair And Square In Love' and 'There's Honey On The Moon Tonight.' That's the first record I ever bought. I was 14 years old."

This was just one of the many stories Brubeck related during this interview.

WHEN WAS THE LAST TIME YOU WERE ON HORSEBACK?

To really ride? Just after the war, in 1946. My dad said he needed me to take the cattle to the mountains. In those days in California, you took the cattle from the valley to the high meadow in the Sierra Nevada’s. So I went along with him.

I was hurting so much after about four hours of riding, that I got off my horse and was leading it. My dad was way ahead of the cattle, and he had eyes like an eagle. I saw him coming back through the cattle. He said, "Get back on that horse! No son of Pete Brubeck's gonna be seen leading a horse!"

I said, "Dad, I'm so sore. I can't."

"Well, get in the truck, put the horse in the track, but don't let me see you leading the horse!"

And that night I had to sleep on the ground with just my saddle blankets and my saddle for a head pillow. I was back home, but I wasn't ready for it. I'd been in the army four years, and I wasn't ready to come back to this.

YOU WERE IN PATRON'S ARMY, WHICH WAS THE CAVALRY.

But at this point it was tanks.

YES, AND YOU PLAYED MUSIC.

That was a lucky break for me. The Red Cross girls asked if anybody could play the piano. I volunteered and played for months. The front was--you could hear it all night and all day--right up the hill. I was supposed to go there. It was a bad mission that all of us were hoping we wouldn't get into, but we knew that's where we were headed. I got pulled out of that with two other musicians who were with me and told to start a band.

Most of my guys were wounded, guys who came back behind the lines. While they were recuperating, if they were musicians, they would send them to see me. That's how we formed the band. Most of the guys had Purple Hearts. I didn't, but that band was able to play for frontline soldiers. It's a tough audience when they know they're going into battle in the morning. If they looked up and saw those Purple Hearts on the guys playing, they'd know these guys.

WHAT SONGS DID THEY WANT TO HEAR?

I wrote quite a few, and then we'd play the popular songs of the war days. The day we crossed the Rhine at the Remagen bridgehead, the army had taken the bridge but decided it was too weakened from some dynamite that had been set on it. So, we went over a pontoon bridge. Incidentally, that bridge was built by my conductor/manager Russell Gloyd's father. He did all the bridge building for Patton. When you hit the bridge, there was a certain rhythm that the trucks made, and I wrote [a melody] the day we crossed the Rhine.

WHAT TIME SIGNATURE WAS THE BRIDGE?

It was in 4.

I'VE BEEN ON TRAINS THAT WERE IN 7.

Trains are wonderful places to write. Duke Ellington loved to sit over the wheels in the back of the car, and he'd sit up all night. I sat up with him at night, and you get into a different kind of feeling.

WHEN YOU LOOK BACK TO THE RANCH, THERE'S A WORK ETHIC THAT COMES WITH HERDING CATTLE. CERTAINLY, FROM YOUR FATHER YOU INHERITED A WORK ETHIC. WHICH IS MAYBE WHY, AT 82. YOU'RE STILL GOING ON THE ROAD.

Exactly. He worked so hard. In the summer, he usually got up at 3 in the morning, rather than get the cook up. There was a 45,000-acre cattle ranch. It was huge, and you had to get up early. In those days, before we had trucks, you had to ride where you were going to work, and that could be a long ride. I can just hear and see the guys all half asleep on their horses.

I played a concert last year up in the mountains near where I used to live. There's a winery up there, Stonebridge. On the way up I was going by roads where I had driven cattle, and all those memories came back to me. My mind is always going back to when I started playing in all the mining towns. I would come in after a job playing way up in the mountains. My dad would say, "Take off that tux and put on your jeans. I need you." So I wouldn't even go to bed.

DID THE CATTLE OR THE HORSES EVER INSPIRE MUSIC?

Yeah, the hoofbeats of the horses. I'd put another rhythm against the gait of the horse. You'd be riding miles with just the sound of the horse's gait.

My first published pieces were called "Reminiscences Of The Cattle Country." There was one called "Breaking A Wild Horse" that was pretty wild. And one called "Dad Plays The Harmonica" that's in three keys and starts the way my dad always did when he picked up the harmonica. If you want to hear them, John Salmon plays them. (John Salmon Plays Dave Brubeck Piano Compositions on the label Phoenix.) He plays all my music that's printed.

DID YOUR FATHER ENCOURAGE YOU TO GO TO THE COLLEGE OF THE PACIFIC AND PLAY MUSIC?

I didn't want to go to college, and he didn't want me to go, but both of my older brothers had gone through college. My mother, being a college graduate, insisted that I had to go. My dad said, "If he's gotta go to college, he should study to be a veterinarian." I registered at the College of the Pacific as pre-med, but the zoology teacher told me, "Brubeck, next year go across the lawn to the conservatory, because your mind is not in this lab." I took his advice and went across the lawn. I can see those buildings just like they were in 1938. That's where my Institute is.

Currently, Brubeck spends what time he can with the five students at the one-year-old Brubeck Institute at the College of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif. "I wouldn't call them my students," he says. "Christian McBride is the artistic director of the Institute, and J.B. Dyas is the executive director. I'll come out for a couple of days or stay a week, playing sessions with the kids or lecturing, which is mostly answering questions.

"Those kids are so great," he continues. "All 75 who came to audition were fantastic. One kid played 'Giant Steps' at about the fastest tempo you ever want to hear, and that scared me. For him to play it slow would've scared me. He's the pianist, just turned 18. Fabian Almazan from Cuba. He's so advanced. I can't believe what I hear from these students.

AFTER THE WAR, WHEN YOU WERE A STUDENT AT MILLS COLLEGE, WHAT WAS THE MOST VALUABLE LESSON THAT DARIUS MILHAUD TAUGHT YOU?

He said, "Even though you have no background in European music, no training and you can't read music, you've got to be a composer, and you've got to figure it out largely on your own. I can teach you counterpoint and fugue, but at your age (I was 26 then) you'll never pick up a real European background. But you've got to be a composer, and you're going to be a composer!"

He saved me from being discouraged. You can be discouraged when you've come out of the service and you don't have a job. One day he said, "How many jazz students are in the composition class?" We raised our hands. He said, "I want you to write for jazz orchestration." So that's where the octet came from. It was pretty far out. We played just a few concerts. The fast was in front of the girl students in assembly.

When we could no longer work with the octet, my wife wrote to different schools on the West Coast, and the quartet started playing colleges. We're going back this year to Oberlin College for the 50th anniversary of Jazz At Oberlin. That was the first big college concert. That was just the kids in school wanting to hire us, and the campus radio station recording us and putting that out on Fantasy Records.

Another portrait near Brubeck's music desk is a black-and-white drawing of his long-time band-mate, alto saxophonist Paul Desmond. They met when Desmond was a student at San Francisco State. Desmond joined the octet and carried on with the quartet. Brubeck's albums for Fantasy in the early '50s were mostly recorded live, and already on these first records he was getting into music that was polytonal mad polyrhythmic.

Also framed is the original portrait of Brubeck from a 1954 cover of Time magazine. The cover story looked at how popular "modern" jazz had become to a young audience, especially the quartet's appeal to college kids on a campus concert circuit.

"Ellington, Basie, Kenton and others were playing in colleges, but they weren't playing concerts. It's dangerous to say there were none before us, but I don't know of any," he explains of his appeal on campuses. "My wife figured that college kids don't have the time or money to travel where they could hear you. And if you go to a campus, a lot of times it was a free concert. But people started saying that I only appealed to college students. That wasn't true at all. We were playing the top jazz places like Birdland, the Blackhawk in San Francisco. In Harlem we played the Apollo. We had a big following in the black community."

YOU ADDRESSED RACIAL ISSUES EARLY ON. THE MUSICAL YOU WROTE WITH IOLA, THE REAL AMBASSADORS, IS A CALL FOR HARMONY AMONG ALL PEOPLE.

I wouldn't play unless it was integrated. We cancelled a lot of dates, and we integrated a lot of schools by just refusing to play until they allowed us all to play. Eugene Wright would be the first black who performed with the group. It was before basketball and football players were integrating schools. The quartet integrated a lot of schools, and it wasn't just the South. There were plenty of places that had segregation in the North.

Most eye-catching of all the pictures in Brubeck's music room is the original Neat Fujita abstract painting for the cover of Time Out, a 1959 experiment in polyrhythm’s. As bassist Eugene Wright navigates through the cross-currents of drummer Joe Morello, straight-ahead 4/4 counterpoints with 3/4, 6/4, a passacaglia or other classical echoes. Brubeck's "Blue Rondo A La Turk," inspired by a groove Brubeck heard played by Turkish street musicians, is in 9/8, subdivided 2-2-2-3 and alternates with passages in 4/4, all in the form of a classical rondo. And it all quite compellingly and charmingly swings.

Time Out became one of the best-selling jazz albums ever. Desmond's "Take Five" was even released as a single. Over the next five years, mostly for Columbia and mostly with the quartet, Brubeck recorded almost 20 albums, including four more "Time" concept albums.

Time Out's sequel was Countdown--Time In Outer Space, dedicated to astronaut John Glenn. Time Further Out followed with a Joan Miro painting on the cover and two more of Brubeck's hits, "It's A Raggy Waltz" and "Unsquare Dance." Time Changes and Time In completed the Time Series--being re-released by Columbia/Legacy, remastered and with new material in a box this fall.

"Take Five" is a must-play at every Brubeck concert.

DID YOU SAY TO PAUL DESMOND, "LET'S DO SOMETHING IN 5?"

Yes, but it was Joe Morello's beat. "Take Five" was supposed to be a drum solo. I heard Paul backstage at times when Joe would start that beat, just playing against it. I said to Paul, "I've got this album ready to go, but being that Joe's got this beat and you've played against it, you do the tune in 5." When he arrived at my house in Oakland, the first thing he said when he walked up the stairs was, "I can't write anything in 5." I said, "I've heard you playing with Joe in 5. Didn't you write any of that down?" He said, "I wrote a couple of things down." He played them, and I said, "We put these themes together and we've got a typical jazz format of a tune." That's how "Take Five" was born.

WHAT ADDICTED ME TO JAZZ FROM TIME OUT WAS NOT "BLUE RONDO" OR "TAKE FIVE," BUT THE TUNE IN BETWEEN, "STRANGE MEADOWLARK."

More and more people have told me that. It makes me feel good. It's a little strange. It's 10-bar phrases instead of eight. Rhythmically, there's nothing complex about it, but it seemed to belong on that album.

MILES DAVIS RECORDED YOUR TUNE "IN YOUR OWN SWEET WAY," AND ON MILES AHEAD, IN ONE OF THOSE SUITES IS YOUR TUNE "THE DUKE," MILES RECORDED KIND OF BLUE THE SAME YEAR AS TIME OUT. YOU WERE BOTH STARS ON COLUMBIA, BUT YOU NEVER MADE AN ALBUM TOGETHER.

Isn't that funny? We played so many concert dates and nightclubs where we'd play every night for a couple of weeks. He helped me when he played those tunes, because other guys started playing them.

People will say to me, "How come more of your tunes aren't being played? There's hundreds of them!" And I don't know--because there are better tunes than "In Your Own Sweet Way." There are so many of my tunes that I don't play, because I'm always playing the next one.

Classical Brubeck is his other side. He's composed dozens of smaller and larger "classical" works, which often are also religious works--like the three new pieces. "Beloved Son" is an Easter oratorio. "Voice Of The Holy Spirit" also comes from the gospels. "Pange Lingua Variations" reworks an ancient song. Nonetheless, Brubeck's jazz side always comes through, like the several moments when the London Symphony Orchestra is heavily Biblical and the quartet leaps in swinging.

"These guys come in and roar!" he enthuses. "There's one point [in 'Voices Of The Spirit'] where I laugh so hard when I hear it. It's the 'New Wine' section. It's where Peter is saying, 'These men are not drunk as you suppose,' and when Bobby Militello comes in, he sounds like a drunk walking through a bar."

WHAT IS "PANGE LINGUA"?

"Speak, O My Tongue!" It's the oldest western theme that people know about. It goes back to Jerusalem. It was a Jewish chant that became a Roman march. And then through Pope Gregory or some way, it got into European music. The actual themes are all from Gregorian chant. The Church of the Blessed Sacrament asked me to do six variations.

FROM WHERE DOES "VOICE OF THE SPIRIT" COME?

It's the wildest section of the Bible. I have the chorus speaking in 12 different languages at one point. I had a friend who was a linguist, and I asked him "Wouldn't it be great that I have something in tongues for the choir to be singing?" He said "I have friends all over the country and the world who will give you early Persian, Sanskrit or whatever you want." The sentence they're saying is "God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son" in all these different languages.

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL MOMENT ON THE ALBUM COMES AT THE LAST. IT'S YOU PLAYING A PIECE CALLED "REGRET." WHAT DO YOU REGRET?

I regret a lot of things. I regret World War II.

IRONICALLY, MUSIC SAVED YOUR LIFE.

That's for sure. But I lost a lot of friends.

DO YOU EVER CONSIDER THAT MUSIC ALSO PROLONGED YOUR LIFE? YOU CAN'T BE HERDING CATTLE WHEN YOU'RE 82. YOU'RE PLAYING MORE GIGS ON THE ROAD THAN MUSICIANS HALF YOUR AGE.

Yeah. We're booked constantly way ahead. That's starting to scare me. What if I'm not around? But I feel ready to go, and that's all you can do, just keep going.

Copyright - DownBeat