America’s original ambassador of cool.

By Naresh Fernandes

Originally published 2012. Updated 2018

The Hindu is an English-language daily newspaper owned by The Hindu Group, headquartered in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. It began as a weekly in 1878 and became a daily in 1889. It is the second most circulated English-language newspaper in India, after The Times of India.

Few musicians have embodied the interrogative, internationalist spirit of jazz as perfectly as Dave Brubeck, the composer and pianist who died on December 5 at the age of 91. During the course of his seven-decade career, jazz evolved from being popular dance music into an esoteric art form. Brubeck was among the key figures driving that transformation. He expanded the vocabulary of jazz, a melting-pot music from the melting-pot nation of the United States, by seeking out and folding in musical ideas from a vast array of cultures.

Even as he steered jazz in new directions, he persuaded his listeners to take the journey along with him. That was clear from his “Time Out” album, recorded in 1959. Many of the tunes it featured — “Take Five,” “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” and “Three To Get Ready” — employ unusual time signatures that challenged expectations. But Brubeck wrapped these unconventional devices in rhythmic and melodic structures that were so compelling, audiences were enchanted. “Time Out” became the first jazz album to sell more than a million copies.

Ironically, Brubeck’s initial explorations of cultures beyond the borders of the U.S. were made possible by the heightened suspicions of the Cold War. In 1956, the U.S. Congress sanctioned funds for an initiative called the President’s Special International Program. It was designed to send U.S. artists around the world to demonstrate the vibrancy of American culture. Jazz quickly became the programme’s centrepiece. Jazz, after all, was the only home-grown art form the U.S. could boast of.

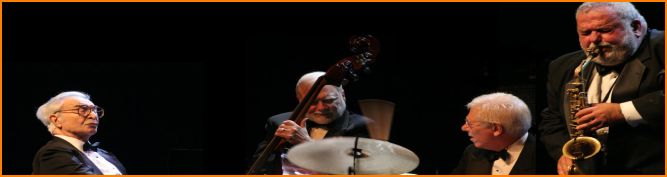

In 1958, the U.S. State Department dispatched the Dave Brubeck Quartet — which included the saxophone player Paul Desmond, the drummer Joe Morello and the bassist Eugene Wright — on its first international tour. It would take the musicians through 14 countries, including Poland, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq and leave an indelible imprint on the group’s music. “Our contact with music from other countries influenced the output of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, including our experiments in odd time signatures,” Brubeck recalled in an interview on the eve of his 90th birthday.

Later that year, Brubeck distilled the sounds he’d heard on the road into an album called Jazz Impressions of Eurasia. The titles of the tracks reflected some of the destinations he’d visited: “Brandenburg Gate,” “Calcutta Blues” and “Marble Arch.” The tunes, he wrote in the liner notes, weren’t intended to merge foreign musical traditions with jazz. Instead, “as the title indicates, I tried to create an impression of a particular locale by using some of the elements of their folk music within the jazz idiom”, he explained.

India, it’s clear, influenced Brubeck quite profoundly. The quartet was in India from March 31 to April 13, 1958. They kicked off their tour in Rajkot and went on to perform in Delhi, Mumbai (Bombay), Hyderabad, Chennai (Madras) and Kolkata (Calcutta). In several places, they had jam sessions with local musicians. In Chennai, for instance, the group went to the studios of AIR and broadcast their musical interactions with the mridangam maestro Palani Subramania Pillai. One night in Mumbai, they had a long discussion with prominent Hindustani classical musicians, including sitar player Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan. Then they picked up their instruments to put their new knowledge to work. “We all felt that given a few more days, we would either be playing Indian music or they would be playing jazz,” Brubeck wrote later.

India, in turn, was vastly charmed by the four musicians. The men strolled through the streets, chatting with fans and sitting in with local musicians. Stories about their exploits still do the rounds. One tale that is still recounted involves the evening Brubeck walked into Mumbai’s Ambassador Hotel and heard Bangalore pianist, Edward “Dizzy Sal” Saldanha, playing his heart out. Brubeck was so impressed, he wangled a scholarship for Saldanha at the famed Berklee College of Music in Boston. Brubeck paid his own money to send the Indian to a rigorous jazz summer school before his Berklee term began.

Brubeck’s empathy for other cultures was rooted in a deep appreciation of his own country’s rich ethos — and his pain at its shortcomings. He was especially sensitive to racial discrimination and refused to play at segregated venues (to significant financial disadvantage). Four years after his India visit, he elegantly exposed the hypocrisy of the State Department jazz tours which put African-American musicians in the spotlight as an example of U.S. democracy in action, even though blacks still weren’t allowed to vote in the U.S. south. In 1962, Dave Brubeck and his wife Iola got together with Louis Armstrong and other jazz stars to produce a jazz opera pointing out these paradoxes. Their witty, stinging indictment of the Cold War jazz project was called The Real Ambassadors. With Brubeck’s passing, jazz has lost one its most persuasive emissaries.